- Home

- David Fajgenbaum

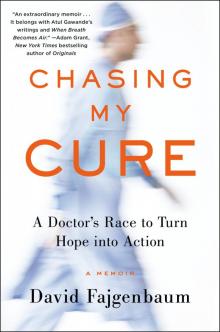

Chasing My Cure

Chasing My Cure Read online

“I could not put this book down. Dr. Fajgenbaum is an inspiration, and Chasing My Cure is a page-turning chronicle of living, nearly dying, and discovering what it really means to be invincible in hope.”

—ANGELA DUCKWORTH, New York Times bestselling author of Grit

“This book is so gripping that I read it in one sitting—and so moving that I can’t stop thinking about it months later. It’s an extraordinary memoir, filled with wisdom, by a doctor who came face-to-face with his own mortality. It belongs in rare company with Atul Gawande’s writings and When Breath Becomes Air.”

—ADAM GRANT, New York Times bestselling author of Give and Take and Originals and co-author of Option B

“Chasing My Cure is a medical thriller that grapples with supreme stakes—real love, bedrock faith, and how we spend our time on earth. Fast-paced and achingly transparent, David Fajgenbaum’s deeply thoughtful memoir will have you rethinking your life’s priorities.”

—LYNN VINCENT, New York Times bestselling author of Indianapolis and co-author of Heaven is for Real

“This is a riveting story of a remarkable journey of one persevering through illness to medical discoveries and recovery. It’s a tribute to Dr. Fajgenbaum’s rare qualities of spirit and intellect, the support of his family and friends, the power of modern science, and the role that patients can play to find new treatments. Chasing My Cure is mesmerizing.”

—J. LARRY JAMESON MD, PhD, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

“This is a fascinating true-life story of a young doctor who, stricken with a rare, life-threatening disease, takes matters into his own hands and, with total focus, finds a cure….An informative and inspiring read.”

—ANDREW WEIL, MD

“I was riveted from the very first to the very last page of this extraordinary story of life, assumed death, resilience, and hope. I am convinced that through his incredible journey, David Fajgenbaum has acquired ‘superpowers’ that will no doubt shape the lives of others, now and well into the future.”

—NICOLE BOICE, founder of Global Genes

“Chasing My Cure is an extremely powerful story about turning fear into faith and hope into action. David Fajgenbaum’s ferocious will to survive and his leadership in the face of his rare disease provide a model pathway for others to follow when searching for cures of their own.”

—STEPHEN GROFT, PharmD, former director of the Office of Rare Diseases Research, National Institutes of Health

“A remarkable and gripping story of how a potentially fatal and rare illness inspired the patient to commit himself as a physician/scientist to search for its cause and cure. Dr. Fajgenbaum’s description of his journey is a tale of courage, dedication, and brilliance that will enthrall and fascinate its readers.”

—ARTHUR H. RUBENSTEIN, professor of medicine, the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

“Inquiring physicians have discovered much from studying patients with rare diseases, but rarely has the physician been the patient. Dr. Fajgenbaum tells the remarkable story of his own mysterious, nearly fatal multisystem disease and his brilliant deduction that a long-known drug may be the cure. This book—part detective story, part love story, part scientific quest—shows how one indefatigable physician can bring hope to patients who suffer from a rare disease that is barely on the radar screen of medical science.”

—MICHAEL S. BROWN, MD, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1985

“David Fajgenbaum, a self-proclaimed ‘rare disease quarterback,’ shares with us his extraordinary story of assembling a team and a framework to conduct unprecedented collaborative research. In his deeply personal memoir, he makes plain the urgency of hope, and explores how the human spirit might transcend suffering to inspire communities to take collective action against seemingly insurmountable odds.”

—JOHN J. DEGIOIA, president, Georgetown University

“Dr. Fajgenbaum has taken a tragic personal situation and turned it into a story that provides a model for all those who want to improve treatment of rare disease. Indeed, the lessons are not only good for people concerned about rare disease, but also for anyone dealing with illness or considering doing something to change the biomedical science enterprise.”

—ROBERT M. CALIFF, MD, former commissioner, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Chasing My Cure is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright © 2019 by David Fajgenbaum

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Fajgenbaum, David C., author.

Title: Chasing my cure : a doctor’s race to turn hope into action : a memoir

/ David Fajgenbaum, M.D.

Description: First edition. | New York : Ballantine Books, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019011796 (print) | LCCN 2019012931 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524799625 (Ebook) | ISBN 9781524799618 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Fajgenbaum, David C.,—Health. | Lymph nodes—Cancer—Patients—United States—Biography. | Physicians—Diseases—United States. | Physicians—United States—Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | PHILOSOPHY / Mind & Body. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Death & Dying.

Classification: LCC RC280.L9 (ebook) | LCC RC280.L9 F35 2019 (print) | DDC 616.99/4460092 [B] —dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019011796

Ebook ISBN 9781524799625

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Jo Anne Metsch, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Joe Montgomery

Cover photograph: Masterfile

v5.4

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Afterword

Photo Insert

Dedication

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Resources

AFTER YOU’VE MASTERED the basics of technique—hand placement, head tilt, and timing—and after you’ve accepted the inevitable feeling of shattering ribs beneath the heels of your hands, the hardest thing about performing CPR is knowing when to stop.

What if one more pump could do it?

Or one more after that?

When—no matter how hard you push, how hard you hope and pray—that pulse just will not return, then what comes next is entirely up to you. The life has already been lost. But hope hasn’t been, not necessarily. You could keep that alive at least. You could keep doing compressions until your arms and shoulders are too worn out to continue

, until you can’t push hard enough to make a difference, much less break another rib.

So—how long do you try to bring someone back?

Eventually you will remove your hands from the body, eventually you’ll have to—but eventually isn’t a number. It isn’t guidance. You won’t see it in a CPR diagram. And it doesn’t even really answer “when” so much as “why.” When you eventually stop, you stop because there’s no more hope.

That’s what makes the decision so difficult. Your effort allows you to hope that life is possible, and your hope inspires you to push even harder. The three of those things—hope, life, and effort—chase one another, keep one another moving around a track.

I have performed CPR twice in my life. Both times, the patients were nearly dead when I began my relentless chest compressions and prayers. And both ended up dying. I didn’t want to stop. I wish I was still going right now. And I continued to hope that I’d see a pulse appear on the heart monitor even after I had stopped my chest compressions. But hoping and wishing are often not enough. Hope can be a force; but it isn’t a superpower. Neither is any part of medicine, much as we’d like it to be.

It can feel like one, though.

When I set out to be a doctor, I had already borne witness to incurable disease and inconsolable sadness—my mother had died of brain cancer when I was in college—but I was still optimistic about the power of science and medicine to find answers and cures. Because to be honest, long after I could reasonably blame it on youth and naïveté, I basically believed in the Santa Claus theory of civilization: that for every problem in the world, there are surely people working diligently—in workshops near and far, with powers both practical and magical—to solve it. Or perhaps they’ve already solved it.

That faith has perverse effects, especially in medicine. Believing that nearly all medical questions are already answered means that all you need to do is find a doctor who knows the answers. And as long as Santa-doctors are working diligently on those diseases for which there are not yet answers, there is no incentive for us to try to push forward progress for these diseases when they affect us or our loved ones.

I know better now. I’ve had a lot of time over the past few years to think about doctors, and they’ve had a lot of time to think about me. One thing I’ve learned is that every one of us who puts on a white coat has a fraught relationship with the concept of authority. Of course, we all train and grind for years and years to have it. We all want it. And we all seek to be the trusted voice in the room when someone else is full of urgent questions. And the public expects near omniscience from physicians. But at the same time, all of that education, all those books, all those clinical rotations, all of it instills in us a kind of realism about what is and what is not ultimately possible. Not one of us knows all there is to know. Not even nearly. We may perform masterfully from time to time—and a select few may really be masterful at particular specialties—but by and large we accept our limits. It’s not easy. Because beyond those limits are mirages of omnipotence that torture us: a life we could have saved, a cure we could have found. A drug. A diagnosis. A firm answer.

The truth is that no one knows everything, but that’s not really the problem. The problem is that, for some things, no one knows anything, nothing is being done to change that, and sometimes medicine can be frankly wrong.

I still believe in the power of science and medicine. And I still believe in the importance of hard work and kindness. And I am still hopeful. And I still pray. But my adventures as both a doctor and a patient have taught me volumes about the often unfair disconnect between the best that science can offer and our fragile longevity, between thoughts and prayers and health and well-being.

This is a story about how I found out that Santa’s proxies in medicine didn’t exist, they weren’t working on my gift, and they wouldn’t be delivering me a cure. It’s also a story about how I came to understand that hope cannot be a passive concept. It’s a choice and a force; hoping for something takes more than casting out a wish to the universe and waiting for it to occur. Hope should inspire action. And when it does inspire action in medicine and science, that hope can become a reality, beyond your wildest dreams.

In essence, this is a story about dying, from which I hope you can learn about living.

IN MY SECOND year of medical school I was sent out to a hospital in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, an old steel town that had bottomed out in the nineties but had since bounced back into a vibrant, small community. I could relate. I had also gone through my own dark valley—losing my mother to cancer six years prior—and now I felt like I had climbed up and out onto the other side. My mom’s death had inspired me to go into medicine in the first place; I had dreamed of helping patients like her, and I yearned to take revenge on her disease.

Picture me as a warrior in the battle against cancer, training so I could lay waste to the so-called emperor of all maladies, the king of terror. Picture me sharpening my tools and arming for war, stoic and full of wrath.

But first picture me on my obstetrics rotation, and absolutely terrified. On this particular day, I felt less like a warrior than like an actor. I had to keep rehearsing over and over in my head what I needed to do. I reviewed my steps, practiced my lines, worked through my checklist, and tried to remember how to play doctor. It really did feel like I was about to go onstage. The hospital room curtains had been thrust open, and the sun was streaming in, throwing a heavenly kind of spotlight on the first-time parents and all over the blue covering the nurse had just put down. Though both prospective parents were beaming with excitement, the mother’s forehead glistened with sweat; I’m sure mine did too.

This husband-and-wife team were in their late twenties, which made them older than I was. It crossed my mind that Caitlin, then my girlfriend of three years, and I could find ourselves in this very same position soon enough, and that was a happy, calming thought. But perhaps I looked even more nervous than I thought I did, because the father asked, “This isn’t your first time, is it?”

A scary thing about medicine is that everything in it has a first—every drug has a first patient, every surgeon has a first surgery, every method has a first try—and my life at the time was dominated, daily, by first times and new challenges.

But no, I assured this father-to-be I’d done this before. What I didn’t say was: once before.

Then I was in position. My second Red Bull of the morning had kicked in, and I was ready.

As I cycled through the stages of labor in my mind, I was interrupted by the first sign of the baby—his head.

Don’t drop it, Dave. Don’t drop it, Dave. Don’t drop it, Dave.

And that was that. I guided the baby safely into the world (it’s actually easier than you might think), and I watched him take his first full breath of life. A profound sense of purpose spread through my body, into my limbs, and overwhelmed my senses so that I couldn’t even notice the smell of feces and blood that attends every delivery. It didn’t look like it did in movies. There was a lot more winging it, a lot more fear, a lot more relief.

There would be many times, later on, when I would remember that baby I delivered. What I did wasn’t heroic or complicated or extraordinary by any measure. It was routine. But I had helped new life take flight and that was extraordinary. Too often hospital medicine isn’t about new life—when doctors, nurses, and patients are assembled in a room, the reason is usually dire.

My first rotation working in a hospital where I could see this firsthand had been in January 2010, only a few months before my Bethlehem (Pennsylvania) baby. After four years of pre-med, a master’s degree, and a year and a half of medical school coursework, it was finally time to apply my medical knowledge in situ. No more shadowing, no more observing. I might actually help save lives. I got about three hours of sleep the night before my first day—I couldn’t remember being that amped up since my days of playing football. It was

below freezing and before dawn when I got up to go to the hospital, but my adrenaline practically carried me there. I’d walked through the same entrance and atrium of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania many times before, but today it was totally different. The floors shone brighter. It was larger—or I was smaller. I smiled and waved at the security guards, who met my glee with dutiful reciprocity. They had likely seen dozens of glowing medical students that morning. Each of us, of course, dreaming that we’d be cracking cases and helping patients today like in an episode of House.

My first stop was the psychiatry resident call room, where I was supposed to meet up with what’s called the psychiatry consult service. Basically our job would be to visit patients throughout the hospital whose treating physicians had decided they could benefit from additional psychiatric assistance. Some patients were simply delirious after surgery, but others had said they wanted to hurt themselves, or other people.

Psychiatry wasn’t what I really wanted to be ultimately doing—all I could think about doing was fighting cancer—but I was eager to begin my clinical career on a good note. So I attacked the day with egregious enthusiasm. I greeted a woman a few years older than I—one of the residents—who was already engaged deeply in something on her computer screen. I extended my hand, introduced myself, and announced—unnecessarily—that this was my first rotation.

Then, as now, I was terrible at masking my mood. It has always been so achingly obvious. The resident could probably smell the nervousness on me.

Another medical student came in after me. Well, as I soon learned, he wasn’t exactly a medical student, even though our role there in the consult service would be the same. He was already an oral surgeon; he’d already completed dental school and dental residency. He was now coming back to undertake a few medical school rotations that are mandatory to practice as an oral surgeon. I was competing against someone in his eighth year of medical training.

Chasing My Cure

Chasing My Cure