- Home

- David Fajgenbaum

Chasing My Cure Page 13

Chasing My Cure Read online

Page 13

It occurred to me, between the periodic beeps from my IV pole, that Dr. van Rhee was not saying “I don’t know” to my queries about my illness. He might have said “I’m not sure, let me look that up…” and swiveled over to his computer to plug in the symptoms and dial up some answers. But he didn’t say that. He said “No one knows.”

“Are there any other drugs in development or clinical trials?”

Dr. van Rhee was unfailingly calm and caring when he responded to my most important question. “No, not at the moment.”

“Are there any planned?”

“Not that I’m aware of.”

Dr. van Rhee was the undisputed worldwide expert on Castleman disease, and he didn’t know what initiated the disease or what caused it. Or how to prevent relapses in patients for whom the only experimental treatment in development didn’t work. That meant that no one knew. There were no more appeals. There was no higher bench. He was not flattering himself by speaking on behalf of the world’s knowledge of my condition. He was that knowledge. He didn’t just have authority; he was the authority.

As a medical student, I could select the correct answer to each of these questions for what seemed like every disease, but not this one.

“I know elevated interleukin 6 is supposed to be the problem, but blocking it hasn’t worked twice now and my interleukin 6 tests were normal during my presentation and relapses. Is it possible that interleukin 6 isn’t the problem for all cases?”

“It’s possible.”

That was it. It was possible. Anything was possible.

I knew what he meant. I knew the language that doctors use: the careful truth telling, the hedging, the open-endedness. I’d spoken that language before. Now that it was directed at me, it didn’t feel nearly as careful, or open-ended, as I’d once assumed. Instead, the words felt like they were casting me out of the room, out of the hospital entirely. I’d been consigned to the plane of possibility. Anything was possible, because no one knew. I was on my own.

A proper patient might have taken Dr. van Rhee’s pronouncements with humility and acceptance, but no one knows didn’t cut it for me. There are things we can change and things we cannot change. We need either the grace to accept them, the ignorance to not know the difference, or prayers to find another expert who has the answers. I am not graceful. I was no longer ignorant of the realities of iMCD. And I was getting tired of praying.

A whole mental structure built on faith and expectation—or hubris—collapsed for me that day. When Dr. van Rhee entered that room to discuss my disease rationally—doctor to emerging doctor—I had believed there had been a vast, unseen, but highly coordinated system of scientists, companies, and physicians working diligently to cure my disease. Every disease, actually. Of course there was—right?

Like Santa and his elves working to grant wishes to every good boy and girl in the world, I imagined that for every problem in the world, a highly qualified team worked diligently, perhaps in a workshop, and it operated out of sight, out of mind, right up until the moment that it solved the problem. Right on schedule, deposited in your living room, and wrapped in a bow, the problem is solved, revealing the magic of the workshop’s efforts. Google reinforces this belief. For every question you can think of, Google provides an answer—and often data to back it up—with a speed and precision that inspire confidence, if not always comfort. The frequent news about medical breakthroughs feeds this optimistic illusion: You assume that someone, somewhere has already figured out the answer to every medical question you could ever pose or, if not, that a team is hard at work solving your particular puzzle, to meet your particular medical need as quickly as possible. A cure is near; discoveries will happen whether or not you contribute time, talent, or dollars toward them. So, I had waited on the sidelines because I believed others were on the case. But now that illusion was no longer possible to sustain. Not when Santa Claus himself was looking me in the eyes and telling me nothing would materialize, gift-wrapped, to cure me.

Nausea overwhelmed me, partly because of the chemotherapy cocktail that had been slowly dripping into my veins during our conversation, and partly because of the realization that I was completely alone. I was terrified. This was the fourth time in the last two years that I would approach the precipice of death. This time, I knew that I would die, because the only drug in development for my disease had failed to work. The harsh reality was that the medical community didn’t understand the most basic aspects of my illness—the only thing the medical community “knew” to be true was actually wrong—and the world’s expert in it had run out of ideas and options for me.

Despite the fact that my immune system was consuming all of my energy as it attacked my organs, despite the accumulated toxins and chemotherapy that made my thinking cloudy, I had the most clear and important thought of my young life: I could no longer just hope that my treatment would work. I could no longer rely on the previous research. I could no longer hope someone else, somewhere would perform research that would lead to breakthroughs that could save my life. If I were to survive again—and to survive long term—I had to get off the sidelines and act. If I didn’t start fighting back to cure this disease, no one else would and I would soon die. I would never get to marry Caitlin or have a family with her. Dr. van Rhee was the foremost expert in the world on Castleman disease—Santa himself—but the foremost expert in the world can only ever know as much as the accumulated knowledge in the world. If the answers have not yet been uncovered, then the foremost expert couldn’t possibly know them. These answers weren’t Google-able, and prayers couldn’t help to find the doctor who knew them. No one knew. Even worse, there were no promising leads being chased. The limits of Dr. van Rhee’s potency were the limits of the world. They were also now my limits, and other patients’ limits too.

My body was dying. I was in overtime. I was spent. But at least I wasn’t on the sidelines anymore. Now I was in the game, and I knew what I had to do. I would simply have to increase the knowledge of the world about iMCD.

My sisters, Caitlin, and Dad were seated around the bed and had listened to Dr. van Rhee’s every word. They all had their hands on their heads and stared down at the floor between long blinks and deep breaths.

I interrupted the silence by saying something that I hadn’t ever voiced before but knew was my only choice. In hindsight, it reminds me of the final promise I made to my mom. “If I survive this, I’m going to dedicate the rest of my life—however long that may be—to answering these unknowns and curing this disease.”

I heard myself like I was Winston Churchill vowing to fight on the beaches, but my pledge to defeat Castleman disease was less than stirring to Caitlin and my family. Those words in the hospital room landed with a polite thud. They each gave a half smile—a kind of smile that I had seen before. The one where they purse their lips and close their eyes. They were just focused on me making it through this relapse. They weren’t interested in heroics. They too knew that we were in yet another overtime, and that the future no longer pertained.

I couldn’t blame them. My family had watched this monster of a disease take me to the brink of death three times. They had also lost some of their optimism eight years before, when our mom’s brain cancer relapsed after one year of treatment on the only promising drug at the time. With no other options, she died a few months later. Here I was, fifteen months after last being ravaged by my disease, and the only promising drug was not working. This was a situation familiar to everyone in that room.

But this was the moment when I realized that I was finally done with the passive kind of hope, the hope that waits for Santa Claus and gets in the way of action. To be sure, passive hope had helped me through multiple relapses. I don’t think I would have survived the third one had I not met the patient in Dr. van Rhee’s clinic who looked so healthy; his example sustained me.

But here, at last, I understood that hope on i

ts own is often not enough. In my case, hope that my treatment would work and hope that some researchers somewhere would unravel iMCD impeded my taking action. And why not me? Suddenly, I saw that the road to what I was hoping for may be long, and I knew it was likely that I would never get to the hoped-for end. But I needed to start trekking.

Now I had to figure out what actions to take. And, of course, I had no guarantees that I would figure anything out or that my final days would not be spent working in vain to answer the unknowns of Castleman disease. In fact, I expected that my time would probably run out before I could make a meaningful impact for myself and other patients, but I wanted to go out swinging; there was no way to know unless I tried. I would make every second count, and my fourth overtime would be bigger than just me fighting to survive—it would be me fighting to extend survival for the thousands of other patients with my disease.

Soon, I began to feel the power of a closed circuit of hope and action: The more I imagined a long future with Caitlin and the possibility of children, the more the stultifying effects of fear and doubt dissipated. Then, action that led to meaningful progress inspired further hope for my future. The more I thought about the thousands of other patients with my disease and the many more who would be diagnosed in the future, the more I was inspired to act. Hope was the essential condition and fuel for my taking action at this point in my life. Fear disintegrates. Doubt disorganizes. Hope clears the way, pushes out the horizons, and gives us space to build structures. My hope was inaugurated by the strength that my family gave me, that Caitlin gave me, and, crucially, that I grabbed by the neck when I knew no one else would and decided to take it. Think it, do it is how I “programmatized” hope, how I turned it into action that I could take and make every day. Hope wasn’t something precious I had to preserve; it was something strong, stronger than I was, that I hitched on to for dear life.

For years, I had interpreted the Pope John Paul II quote I’d found in my mother’s purse—his call to be “invincible in hope”—as referring to being invincible because you can have faith that your hopes and prayers will come true. You just need to trust and wait. I’d read that line as meaning that taking action was almost in opposition to being invincible in hope. But I later found the remainder of the pope’s speech. He went on to say:

Happiness is achieved through sacrifice. Do not look outside for what is to be found inside. Do not expect from others what you yourselves can and are called to be or to do.

I became invincible in hope only after I realized I was called to act on—and with, and through—that hope. I knew what I needed to do.

But first things first: I asked the nurse for a dose of Zofran for my nausea. It’s a lot harder to solve the thing that’s killing you when you want to throw up. Especially when you’re just a lowly medical student. Then I asked Gena if she could get a copy of my blood work. She wiped away her tears and sprang into action, eager to do something, anything that could help her little brother. I needed my test results so I could start studying my disease and also so I could estimate how much time I likely had before I’d be incapacitated by kidney and liver failure—or dead.

Then, I started squaring up to this beast of a disease. With three more days of continuous cytotoxic chemotherapy and then seventeen days of interspersed chemo ahead of me, my hair would soon start falling out in clumps, the way it had before. But I didn’t want to wait for it to fall out again, and I didn’t want this disease or chemotherapy to be the cause for it coming off. I was done being a victim. This time I would act: I asked my dad to buy an electric razor, and he shaved all my hair off, save a small strip of short hair down the middle. I had always wanted a Mohawk. I probably also should have covered my face in camo war paint. I was gearing up for a new kind of battle, one that wasn’t simply about my surviving Castleman disease’s attack—it would involve me counterattacking. And I was reminded of that every time I saw my high-and-tight look in the mirror.

AS THE BIG day approached, I got more and more nervous.

Dr. van Rhee was concerned that I might not be healthy enough and my immune system not strong enough. My dad echoed his concerns, saying I needed more time before I made such a hasty decision. Knowing how disappointed I would be, Dr. van Rhee brought my favorite Trini dish to the hospital that night. It was a great consolation.

But I knew what I needed to do. I knew what I had promised.

Finally, with just days to spare, Dr. van Rhee came back with the results and told me that my white blood cells had reached the threshold we had discussed. It was time.

I left the hospital, got on a plane, and returned to Raleigh.

I wasn’t going to miss Ben’s wedding.

The carpet bombing worked. I recovered again. Don’t ask me how. I don’t know. I’d gone through hell again, and I came back. We didn’t know what treatment to try next, but that didn’t matter as I stood as Ben’s best man at the altar looking out at a congregation that included my father, my sisters, and the love of my life, Caitlin. Pictures of that day show my freshly bald head—not from the chemo, but because I shaved it—and a smile from ear to ear. I almost look deranged. I’m smiling because I’m upright and (mostly) feeling fine, and because I’m there with everyone I love. And because I’m fulfilling one of my promises to Ben from high school that I never thought I was going to be able to keep.

But I’m also smiling for another reason.

With football, I think I may have gotten more sheer pleasure out of preparing for than actually playing the game. The film study, the lifting, the drills, the practice, the meetings, the strategy. It was the same with AMF: I loved whiteboarding in the AMF office about how to expand our reach or improve our services. And in school I’d taken strange (certainly to my friends) satisfaction in sitting at a long table in the library, books ready, pencil in hand, papers meticulously placed across the table, perched on the edge of a marathon study session.

That smile at the wedding? It’s the smile of a man who knows what he’s about to do. It’s the smile before the storm. After round four, all my thinking had been done, now it was time for the doing. I felt like Jason Bourne in the fourth act: battered, bloody, totally broken down—but with a plan. No one more dangerous than someone with nothing to lose and a head full of steam.

The hyperfocus helps too.

* * *

—

After a few weeks recovering in North Carolina, I returned to medical school. I would continue to receive siltuximab and weekly doses of three of the seven chemotherapies that had just induced my remission. We reasoned that maybe siltuximab in combination with these other drugs would work even if it hadn’t worked on its own. And even if my IL-6 levels had been normal previously. I didn’t feel very confident that this approach would work long term, but I just didn’t have any other options.

As I look back, I see that everything that had happened in my life had prepared me for this. I didn’t have the specific experiences to pursue a cure for a disease, but I had the tools. I had the work ethic that bordered on obsession. I had the institutional memory of building AMF, which provided me with a blueprint and confidence knowing I could execute. I would lean on lessons learned from my years as a quarterback to build and develop a team. My master’s at Oxford gave me a framework for studying and answering highly complex questions. My nearly complete medical school coursework and clinical rotations gave me the language, understanding of disease mechanisms, and training that I’d need. What I learned from performing strategic planning for the Penn Orphan Disease Center informed the approach that I’d take. Losing Caitlin when I thought we had all the time in the world and never wanting to lose her again gave me an unrelenting sense of urgency and helped me to prioritize the most important things in life. And, significantly, I had finally internalized the idea that sharing my vulnerabilities would be a good thing and even important for mobilizing others to help. Caitlin and my family gave me all the

love and support I would desperately need.

To take on Castleman disease, I would first need to understand the current state of research: what was known about the disease, what research was being done, and what steps other rare disease groups had taken to advance research for their diseases. I was like a detective who arrives at the murder scene and quickly gathers info from the cops already there. No one had solved the crime yet, but their legwork would be crucial to getting a lead.

Though Castleman disease was discovered in 1954, the only real advance in understanding my subtype had been in pinpointing IL-6 as a likely actor underlying the disease. But for me, IL-6 had not yet proven to be the main issue, so for me, the only real advance since 1954 was a misstep. Inaccurate information about epidemiology and prognosis was on reputable medical resources, including the UpToDate page that I now knew to be ironically and woefully out of date. Other websites weren’t just out of date, they were objectively wrong. There was not a unique International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code to identify and track cases of Castleman disease—so even when doctors diagnosed Castleman disease patients, there was no way to identify them for future research and for the wider medical community to better understand. Many researchers and physicians were using different terminologies to subclassify Castleman disease, and still others lumped all Castleman disease cases together, so readers of published research articles wouldn’t know which subtype the paper was referring to or be able to understand the results in the context of previous research. In short, the state of Castleman disease affairs was a mess.

Messes are worse in science than anywhere else, because science is quintessentially iterative. Everything builds on the past, on the last experiment, on the last theory, on the last results. Common standards of terminology and measurement are the sine qua non of the whole shebang. Basically, you need to be sure everyone is separating the apples from the oranges in a consistent way.

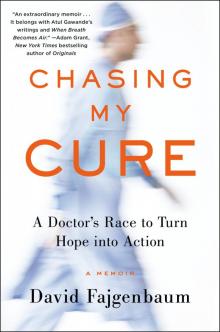

Chasing My Cure

Chasing My Cure