- Home

- David Fajgenbaum

Chasing My Cure Page 15

Chasing My Cure Read online

Page 15

Had I not literally had skin in this game and a time bomb hidden beneath, I can’t say that I wouldn’t have once agreed with this emerging consensus. But of course I did and do have skin in the game. And I could almost hear the ticks. I knew I was doing the right thing, and so I chafed at the idea that I should back down from our radical research approach and stick to patient advocacy. What I tried to explain and show was that in my dual role—physician-scientist in training and patient—I had no choice but to continue at a breakneck pace, and we were in this position because the status quo hadn’t gotten us very far. I understood that I had my professional reputation to lose, but I couldn’t bring myself to care. My illness had liberated me from having to follow many of the unwritten rules that regulate medical research. I questioned the status quo, the accepted way of thinking about my disease, and the way research was being done. Being a physician-scientist-patient gave me a unique lens through which to see more than either perspective on its own. I saw clearly that we scientists and physicians are fallible. And I saw that patients had ideas and concerns that needed to be central to our mission.

Indeed, it would be our modus operandi to engage and involve patients a bit differently than many other organizations did. We wanted to know what research questions were important to them. Maybe not too surprisingly, questions important to patients weren’t always the same as those for physicians and researchers. Patients focused more on quality of life issues, such as fertility and symptom management to be able to return to work, whereas physicians and researchers wanted to uncover cells, pathways, and proteins that could be targeted to extend survival. So we integrated suggestions from both groups on the CDCN international research agenda. We also connected patients with one another through social media, online discussion boards, and periodic in-person gatherings. I didn’t discount for a minute the power of this kind of connection. Meeting another patient in Dr. van Rhee’s waiting room years before had given me the boost of confidence and support I needed to keep fighting.

Plus, patients are sometimes a lot more fun to be around. During our first ever patient webinar, I showed a stick figure cartoon of a man dressed as a castle that I had found on Google. I dubbed him Castle Man and suggested him as a possible unofficial logo for the CDCN. But several patients contacted me afterward to say that the Castle Man was way too puny. They explained that there was no way the hypothetical Castle Man could be a stick figure. Given our battle wounds, they explained, he should be a beast! I couldn’t have agreed more. We subsequently adopted a Castle Man that was much more Beast-like and shared the new cartoon with patients on another webinar. Two weeks later, a patient posted a photo on Facebook of the Beast-like Castle Man tattooed on his shoulder, the first of many patient body parts to host him. If this isn’t patient engagement, I thought, then I don’t know what is. Castleman disease patients had been waiting to come together to fight. They just needed a galvanizing force. I knew that we were going to accomplish big things together.

One patient who was tuned in to that initial webinar would play a particularly large role in our growth. Greg Pacheco and his wife, Charlyn, had founded Castleman’s Awareness & Research Effort (CARE) in 2007. Greg and his board had been doing good work around awareness but weren’t satisfied to stop there. They wanted to be a part of discovering new treatments and were excited by what they saw of the CDCN vision. Soon thereafter, Greg invited us to merge the CDCN with CARE and move forward under the CDCN name. I know now that this was a rather remarkable offer—and a rarity in biomedical research. More often than merge, research groups and foundations tend to splinter into often competitive subgroups. New families affected by rare diseases tend to start new foundations from scratch even when others exist. As a result, individual rare diseases can often have dozens of organizations working in parallel, often with competing agendas, inconsistent objectives, and fractions of the total funding pool to distribute. Greg and his fellow board members were taking a bold step. They could have chosen to maintain the autonomy and familiarity of the status quo rather than join forces with a laser-focused lunatic like me and my intense colleagues. This was like adding Mr. T and the A-Team to a UN peacekeeping mission: You better be ready for fireworks. They were.

As for Frits van Rhee, Arthur Rubenstein, and my decision? After a little deliberation, our choice was simple: We had a common mission—to cure Castleman disease—and collaborative was part of our name. We gladly accepted Greg’s offer. We merged.

It was now time to determine our top-priority research studies. After crowdsourcing sixty ideas from the CDCN community, the scientific advisory board combined, tweaked, and ranked the ideas into a prioritized list of twenty study ideas. The top priority: to search for a possible virus that could be causing iMCD. We reasoned that a virus caused one form of MCD (HHV-8-associated MCD) and that viruses are highly capable of inducing immune system hyperactivation like iMCD patients exhibit. And if we could figure out a viral cause, then we could figure out several other unknowns very quickly, such as the key cell types harboring the virus and potential targets for new therapies.

Armed with our top-priority question, we reached out to the top “viral-hunting” researchers in the world. This step followed through on our mission to be proactive. We didn’t care if these researchers had ever heard of Castleman disease so long as they had the technical chops to chase down a potential causal virus.

Our top candidate, the leading expert on this kind of research, who was at Columbia University, agreed to perform the study. However, he would need twenty frozen lymph node samples from iMCD and UCD patients. Lymph nodes are rarely ever frozen after being resected. Thus, we needed biospecimens from a rare subtype of a rare disease preserved in a very rare way. So we put the CDCN’s network of now more than three hundred members to work, contacting physicians and researchers around the world to see if we could identify these precious samples. After months of outreach, seven institutions based in Japan, the United States, and Norway agreed to contribute twenty-three samples to this study. Altogether, we knew this research would take several years, but it could begin!

* * *

—

I was ready to begin something new now too. Caitlin and I were seeing each other as often as possible—in Philadelphia, in New York, and sometimes in North Carolina, when she traveled with me to get my regular siltuximab and chemotherapy infusions. I had known for years that I wanted to spend the rest of our lives together. Life was better and I was happier with her in it; I knew she felt the same way about me. I had known since seeing her at my bedside during my fourth relapse that I had to stop imagining that future and get on with it! But I still struggled with the decision. I desperately wanted to marry Caitlin, and I knew she wanted to marry me, but was it asking too much of her? The man she’d started dating years before—a carefree quarterback with seemingly full control of his future—was not the man she was with now. Now, I was a critically ill patient fighting for each new day. Now, I was a scientist chasing after life with no guarantees. As ready as I was to propose, I also thought about breaking up with her and pushing her away from me, so that she could find a more stable and predictable and easier life with someone else. She deserved that. But I knew she would refuse and that this would only hurt her worse. I had already denied her twice before. I couldn’t do it a third time. And I wanted so much to be her husband. I started to shop for an engagement ring.

I chose December 16, 2012, as the date I would propose. Caitlin would be visiting and I told her that we had brunch reservations at a restaurant near our favorite park in Philadelphia. I arranged for our families and friends to gather at the nearby restaurant, from which they could see us in the park and at which I hoped Caitlin and I would join them to celebrate after she said yes. On the way out of my apartment, I stopped by the mailroom and “found” a card from my then seven-year-old niece, Anne Marie. I gave it to Caitlin as we walked across the park.

The front of

the card was adorned with multicolor stick figure drawings of Caitlin, Anne Marie, and me. Inside, it read:

Dear Aunt Caitlin,

I am so excited for the wedding and can’t wait for you to be a part of our family.

Love,

Anne Marie

P.S. I’m a really good flower girl!

Involving Anne Marie in my plan felt important, because she and Caitlin were very close. But I now retell this part of the story with a wink and a grin: Even if Caitlin was unsure about saying yes to me, she wouldn’t want to let Anne Marie down. Because even though I thought we were on the proverbial same page about marriage, I was nervous about this dramatic moment. Caitlin covered her mouth with her hands. She was completely shocked.

She said yes. We both cried tears of joy.

Once we’d recovered our poise, we walked to the restaurant to join our families and friends in celebration. Alone together at the end of that amazing day, we spent some time discussing what we’d do next. She was working in fashion in New York but was ready to leave. I was in the throes of medical school with a semester to go, working in the hospital every day, and couldn’t leave Philadelphia. Before she got on her train to New York that evening, Caitlin decided that she’d give three months’ notice to her employer right away and move to Philadelphia to live with me. She’d begin looking for jobs in Philadelphia. We both agreed that we needed at least a year before our wedding so that Caitlin had time to focus on relocating and finding a job before wedding planning ramped up too much. We were so excited!

But the excitement wouldn’t last for long. A week after our engagement, I had my every-six-month PET/CT scan. This time, I did it when I was supposed to. In addition to looking for iMCD activity, PET/CT scans also search the body for cancer, which iMCD patients are at an increased risk for developing. The scan showed that I had a tumor growing in my liver with increased metabolic activity, potentially indicating cancer. My doctors felt that it was probably just a giant ball of blood vessels, like those hemangiomas on my skin, and not actually cancer. Nothing to worry about. We should just rescan in six months, they said. Wait and see. I remember thinking, Why the hell do we do these tests if we disregard the results when they come back abnormal? I had been burned enough times before by human error, physician misinterpretation, and personal avoidance. I wasn’t just going to hope that it was a ball of blood vessels and trust my doctors’ judgment. Especially now that I had a wedding in my future. Surprisingly, I wasn’t afraid. I had learned from my previous experiences that there is no reason to spend energy worrying about an unknown. You might worry much more—or even far less—than you should. I reasoned that it’s far better to spend that energy trying to figure out what the hell is going on. Hyperfocusing on a diagnosis completely pushed out any space for nervousness. Caitlin and I continued to see each other every weekend. We talked about what this could mean, but following my lead, Caitlin remained fairly stress-free. I got a second opinion and pushed for another scan, an MRI, to be done a couple weeks later. In just those few weeks, the tumor had doubled in size. It was growing fast. An understatement: This was not a good sign. The scan also confirmed that it definitely wasn’t a giant ball of blood vessels and it wasn’t going to just go away with hope—it’s a good thing I was done hoping.

A subsequent biopsy revealed that I now had a rare form of cancer called an EML4-ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in addition to my iMCD. At first, I was terrified, though I was also so exhausted and battle-weary from my fight against iMCD that I could barely get the energy up to show my panic. Then, I turned to Google. What is an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor? In just a few minutes, my terror turned to optimism! Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors, or IMTs, can release inflammatory molecules like IL-6, turn on the immune system, and cause symptoms just like those seen in Castleman disease! Maybe I didn’t have the bad luck of being struck by both iMCD and an IMT. Maybe the IMT had been in my liver all along and was the source of all my problems. Maybe it wasn’t on top of my iMCD. Maybe it was what turned on my immune system, which led to my iMCD in the first place. Maybe we could cut it out and my nightmare with iMCD would be gone forever! Maybe this was the missing puzzle piece for all iMCD patients!

The surgery would be intense, so Caitlin moved up her last day of work by a couple weeks, and moved in with me. She was the last person I saw before I went under on my twenty-eighth birthday. We were both scared, but I was also ready for the IMT to come out and possibly bring an end to my battle with iMCD.

Five hours and three units of blood later, 15 percent of my liver—including the cancer—was carefully resected. I had a ten-inch abdominal battle wound to show for it. And the pain to accompany it. The epidural that should have given me relief during recovery had not been properly placed, so I could feel everything when I woke up. There isn’t a scale from one to ten or an appropriate frowny face to describe the pain. I had had my abdominal muscles dissected, a chunk of my liver wedged out, and the remainder of the liver torched with an argon laser, which is basically a flamethrower, to stop the internal bleeding. I watched the clock all night, waiting for the moments every fifteen minutes that I could push the button to administer more pain medication into my veins, but even then I felt seemingly everything. The next morning, a new epidural was placed and the stabbing pain dissipated.

Soon after I got my new epidural, the surgeon came into my room to inform me that based on careful review of the margins of the resected tumor, a small amount of the cancer had been inadvertently left in my liver. I tried to sit up a bit in the bed to make sure I had heard him correctly, but contracting my abdomen felt like being stabbed with a sword. Wait, what? You didn’t get the whole thing out? You closed me up before you confirmed the borders were clear? This is Surgical Oncology 101! I wanted to scream. Instead, I took a deep breath and then quietly but insistently pleaded with him to go back in for the rest of the cancer. Unfazed by my begging, he told me I couldn’t handle another surgery in my state and that the argon laser had likely killed any remaining cancer cells that may have been left behind. I was exhausted from all of the highs and lows. I relented and put my luck in the argon laser’s hands.

As soon as I was well enough, I returned to the hospital to review my previous scans with radiologists to see if this was the missing puzzle piece. Could the liver cancer be the cause of my iMCD and have been there all along? Most directly, did they see any signs of the tumor in previous scans? But no matter how close we looked, we couldn’t see any indication that it was there during my previous episodes. I rationalized that maybe it was just too small to see before, but it actually was there all along, underlying this disease. Now it’s gone and maybe my iMCD won’t come back, I mused. I knew it was a stretch.

My disease’s relentless relapses and now this rather dramatic and health-weakening cancer episode—and in the larger scheme of things, it really did feel like just an episode—had forced my outlook for the future to be quite myopic. I rarely scheduled anything more than three weeks in the future, the interval between my siltuximab infusions. But I was able to complete my final few rotations in time to walk in medical school graduation in May 2013. That was such a happy occasion, and my family—including Caitlin’s parents and brother—gathered to celebrate.

I’d worked a long, long time to earn the right to my next step: medical residency. But suddenly something else held more appeal.

At this point, I had identified the key unanswered questions in the iMCD field, crowdsourced the key studies to answer these questions, and begun to build the infrastructure to advance these research studies, but there was a lot of work still to do and a lot of refinement that could help speed things along. I wanted to explore how these steps could help other rare diseases. Strange as it seemed to many, I decided that business school was what I needed to tackle next. At first, I felt guilty for not going directly to residency, as medical school graduates are ex

pected to do. But here again almost dying had liberated me, this time to do exactly what I wanted to do—right now. My rationale: The research challenges I needed to overcome to save my life and others weren’t as often rooted in medicine as in business, strategy, and management. I wanted to optimize the collaborative network approach I was building for Castleman disease. I also needed to keep pushing my iMCD research forward. The clock was ticking, and residency would have slowed down each of these pursuits.

In retrospect, I see that my decision to put residency on hold in favor of an MBA also demonstrated my newfound interest in and passion for research over clinical medicine. I felt that in medicine, I would have to hope the drugs at my disposal would be able to save a life and rely on existing data to guide my decisions. In research, I could generate the data and the discoveries that lead to a drug that could save a life—perhaps thousands—and insights into why a drug may or may not work. I would use business school to pick up the skills I needed to overcome hurdles in biomedical research and iterate on my approach to make research more efficient, collaborative, and strategic for Castleman disease and, I hoped, many more rare diseases.

I would begin my MBA studies at Wharton in the fall.

“WELL…because it’s a really interesting disease. So little is known. These patients deserve better. Patients…who have the disease.”

“Yeah, I get that, but why did you pick…what’s it called—”

“Castleman disease.”

“Yeah, Castleman disease. Seems kind of random. Do you have a personal connection to it or something?”

“I got introduced to it in med school.”

These were the kinds of conversations I was having when I got to business school. I couldn’t come out and tell the whole truth. I was happy and eager to tell people that I was here to do an MBA to develop the skills I’d need to accelerate research and drug development for Castleman disease, but I couldn’t tell my story.

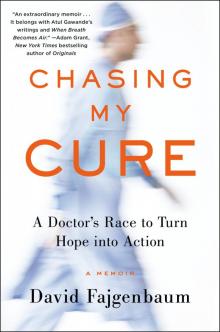

Chasing My Cure

Chasing My Cure