- Home

- David Fajgenbaum

Chasing My Cure Page 17

Chasing My Cure Read online

Page 17

So I didn’t stop to think about it.

If I’m honest with myself, I have to admit I knew this was coming. The liver cancer was an unlikely cause, and the research I had done for the last year suggested that my treatment approach wasn’t going to be able to prevent an iMCD relapse. Fortunately, the year’s worth of data from my monthly blood tests and my new way of thinking about iMCD would come in very handy. And I also now had an international network of colleagues and scientists to tap into. The liver cancer kerfuffle had finally pushed me over the edge and shown me that I had the power to take charge of my care. I would no longer just rely on my physicians and hope that they’d get it right. I don’t mean that with any malice. It wasn’t their fault that there was too little known. Just as I had set out to transform the research field in overtime four, I would need to take command of my own treatment this time. It was impossible for me to imagine lying back and becoming just an object again, just a body. And a failing body, at that.

I was experiencing crushing fatigue (yet again) and organ failure, but to the extent I was able, I jumped into action. I took a leave from business school but took with me what I’d learned. I went into what I think of as Entrepreneurial Treatment Mode. My newly minted physician-friends Grant and Duncan, who were also both pursuing MBAs at Wharton, spent hours on the phone with me discussing the plan of attack, scenarios, data, and potential treatments. Grant was especially helpful during this time because he had a habit that bordered on obsessive: Every time anyone ever said the word can’t, Grant would reply “Why not?” Seriously. Every time. In almost any situation. It wasn’t a childlike, sassy response. Just the opposite. He simply has an innate and constant skepticism of the wisdom of the status quo, an insatiable desire for solutions. Real solutions.

With my new attitude, Grant’s antiauthoritarianism, and Duncan’s do-anything-for-a-friend credo, we made quite the dynamic trio. We vowed that everything—everything—should be on the table, in terms of treatment. No conventional wisdom would go unscrutinized. We didn’t care if the solution required a traditional or a nontraditional approach. In hindsight, Alexander the Great and his solution for the Gordian knot comes to mind. As the story goes, an oracle declared that any man who could unravel the complex knot was destined to become ruler of all of Asia. Countless men tried and failed. When Alexander the Great struggled to untie the knot, he drew his sword and sliced it in half. Problem solved. Prophecy fulfilled.

Armed with our collective fighting spirit, we considered every drug that had ever been approved by the FDA for any use—from cancer to constipation. A drug may have been created to target a parasite or a receptor to decrease heartburn, but we asked what else it could do. Could one of these drugs previously approved for another disease be the magic bullet for me?

If a drug existed that we thought could work, we’d get our hands on it. It’s useful to have a medical degree. And a network of physicians and scientists in your contact list.

In a way, the timing was on our side: When I was in remission, we could try all the new treatments we wanted to, but we wouldn’t really know if they were working until I relapsed or didn’t. It was only during one of these relapses that we had adequate test conditions. When all of my organs were failing, we could try a new drug and know very quickly if my organ function improved—i.e., whether it worked.

Of course, we also understood that my time was limited: The window of opportunity was small. If the drugs didn’t work, I would die. So, if a new drug wasn’t working fast enough, we needed to try to preserve enough time for the combination chemo to have a last chance.

To start, though, we knew we needed to identify a few candidate cell types, cellular communication lines, or proteins that were abnormally increased or decreased during my episodes and possibly critical to the disease to try to target with a drug. Breast cancer innovations are examples of what’s possible when you can do this. One of the biggest breakthroughs in breast cancer was the identification of HER2 on the surface of breast cancer tumors. Once it was clear that the protein was essential to the cellular survival of some cases of breast cancer, drugs were developed that are highly effective if a patient’s particular breast cancer overexpresses this protein. We needed to find a similar “target” in my iMCD. Unfortunately, we had a number of hurdles: We didn’t know what cell type to go after out of hundreds of possibilities, the surface of every cell looks like a forest filled with thousands of proteins to choose from, and the inside of each cell is made up of thousands of proteins interconnected through countless communication lines that could be targeted too. And each cell type—let alone each protein—could take years to study.

Still, we used what we had. In the data I had assembled for the paper I was getting ready to submit to Blood, I looked for candidate cell types, communication lines, or proteins to target. From there, we searched drug databases to see if any existing FDA-approved drugs—regardless of the diseases they were approved to treat—were known to act on these potential targets.

We considered additional criteria as well. Among these potential drugs, we needed to filter out ones that would be slow to show an effect. In an ideal scenario, we’d perform a large study on many patients in which each patient would be randomly assigned to receive one of these drugs, and we’d identify the best treatment. But we didn’t have that luxury. We had only one patient, multiple drugs, and very little data. So we also needed to consider the potential chronology of administering drugs so that one drug’s effect in me wouldn’t confound our interpretation of the effectiveness of a subsequent drug. We needed to balance the chronology with the likelihood of success for each drug to inform our decision. But without any actual data on the effectiveness of these drugs in iMCD to guide us, the probabilities we used were only our best guesses.

Last, we needed to account for the side effect profile of each drug. It’s easier to take a drug with terrible side effects if you know it could work. When you have nothing to indicate it will work, you want to limit potential side effects, which can include death.

* * *

—

I wanted a clear treatment plan so desperately. It feels so great when your doctor has all the answers. No questions. In any other context, the unilaterality might come off as disrespectful. Not in the doctor’s office. A doctor’s speed and confidence are comforting. The speed means she knows exactly what to do, she’s seen this a thousand times, and everything will be fine. You can look at her diplomas on the wall as evidence that the decision was well-informed. You can grab on to the success stories that nurses share about the patients who came back from the dead. You can believe that you’ve been sent to this doctor by a higher power for a reason: to get better. You can pray that your physician will be directed to the correct choice.

It’s absolutely terrifying when you have to figure it out yourself. What if this choice doesn’t work and the second choice would have been the answer? What if I overlooked something that could have swayed me to the right choice? What if my data were wrong? What if my way of thinking was wrong? After all the research, publications, debates with experts, diagrams, and decision trees, there’s no answer key at the end. Ultimately, it was on no one’s shoulders but my own. And my life depended on being right. It would have helped if I had continued my training in a medical residency or was actually practicing as a physician. My limited experiences taking care of patients as a medical student left me severely ill-equipped for these kinds of decisions.

In a word, I was scared. But I understood that you can choose which fear you’ll face. When I was still a participant in the Santa Claus theory of civilization, I was just a little kid waiting for a miracle. Little kids are really good at waiting for good things to happen. They’re also really good at waiting for terrible things to happen. Maybe at night, in bed, when the rhododendron scraping at the window starts to sound a whole lot like claws. What do you do then? Pull the covers up a bit tighter and…wait until

morning. If you’re feeling especially intrepid, maybe you go wake your parents up. But, then again, the hallway has terrors of its own.

The other kind of fear is the kind that comes right before a football game. Yes, those guys are afraid. I know they don’t ever admit it (except when they’ve been retired for a decade, own a few car dealerships, and don’t need to be tough guys anymore). But they are. We all were. But the fear is met with and stirs up a lot of other feelings. It’s the kind of fear that forces you to act—to run through the game plan in your head, to remember the game tape, to think about the opponent’s weak cornerback, whose foot positioning gives away his coverage on every play. Instead of being like the child who has basically two options—freeze or go get help—the football player plans. He’s got a say in things. And he channels his fear into action.

Fear can paralyze. It can also focus.

* * *

—

This relapse was the first time I’d have a chance to test my new hypothesis: that iMCD was an immune hyperactivation disorder, not a lymph node disorder. All things aside, that was exciting. I loved the idea of collecting as much information as possible from my relapse and treatment so that our future research would have some solid clinical evidence to build on. I had a lymph node biopsy performed and blood samples collected for future testing. I was putting my body, piece by piece, into the lab. And I was putting together a ranked list of about twenty possible treatment options. I wasn’t slashing, but I was whittling away at a solution.

Blood tests from each of my previous relapses indicated that T cells were highly activated. T cells are a specialized type of immune cell and key weapons in the body’s immune arsenal known for their ability to cause destruction (including when being reprogrammed by researchers into CAR T cells and directed at cancer, as I mentioned earlier, but also when attacking healthy tissue). We decided that the next drug I tried should target them. The immunosuppressant cyclosporine was known to be able to weaken these cells, and it was FDA-approved to prevent organ transplant rejection. I had even heard of a doctor in Japan—a member of the CDCN—who had tried it with some success in a couple of iMCD patients. I emailed that doctor to get additional information. Compared against the other drugs on my list, it seemed like a promising choice: It targeted activated T cells, had the potential for a fairly quick turnaround, and had a mostly tolerable side effect profile.

I presented my plan to my family and Caitlin. They asked surprisingly few questions and weren’t interested in the details. They just wholeheartedly trusted I was on the right track. If only I could share their confidence. Finally, I called my doctor who had been overseeing my siltuximab infusions in North Carolina to see what he thought. There was a long pause.

“Considering the limited options at this point and the ineffectiveness of the drugs we’ve tried, I think it makes sense.” He liked that cyclosporine had been used in Japan with some success and that the side effects weren’t too bad. The prescription was ready that very afternoon. I wasn’t totally confident it would work, but my other options didn’t seem to be any better.

The dramatic improvement I had hoped for didn’t come. I didn’t get any better. But I didn’t get any worse. Before the cyclosporine, my CRP levels had risen over a few days from 4 to 10 to 40 (I wouldn’t be fooled again by the wrong units: the upper limit of normal was, in fact, 10). Since I had started cyclosporine, it was hovering between 35 and 45 on daily blood tests instead of climbing above 100, as it had each time before. My fatigue, night sweats, and fevers also maintained fairly constant intensity but didn’t seem to escalate. Considering the typical explosiveness of my disease, we posited that this plateau meant the drug was helping. So we waited. But in a few days, as each time before, my fatigue and blood tests started to worsen.

Emboldened a bit by the fact that my first choice wasn’t flat-out wrong, I suggested that we add another treatment, intravenous immunoglobulin, or IVIg. It wasn’t a great choice on its own, but I thought it could be a good add-on. Intravenous immunoglobulin has the dual ability to decrease immune hyperactivation and protect the body from infections. And it doesn’t kill any cells in the lymph nodes or elsewhere, it just has the ability to tamp down immune activation. So if it worked, the success would suggest that immune system activation was the underlying culprit, not something intrinsic to my enlarged lymph nodes.

I felt better within hours of the IVIg infusion. The fatigue subsided. The nausea passed.

I resisted celebrating. I considered the possibility that my mind was tricking my body: the placebo effect. I considered the reality that it was unlikely I’d just unlocked a secret of a disease that had stymied researchers for decades.

But the improvements in my blood tests were dramatic and undeniable. My level of CRP—the greatest marker of my disease and a sign of inflammation—had plummeted from 42 to below 10, back to normal. I had never seen such a large improvement in CRP in such a short period of time. I’d seen it worsen by that much that quickly but had never seen it improve this way, because it is very difficult to completely neutralize whatever is causing such intense inflammation. Remarkably, these results suggested that we had done that here. And other abnormal laboratory tests, like platelet count, albumin, hemoglobin, and kidney function, all returned to normal ranges. Except for some fatigue and night sweats, I was normal again. And for the very first time, we’d reversed my relapse without chemotherapy.

Sitting with Caitlin in our apartment living room and reviewing the numbers, I wept with happiness—for myself, for Caitlin, and for everyone down in Arkansas, everyone who had been in touch to share stories and information about the disease in their own lives.

The case was far from closed, but it was starting to get very, very interesting. This was bad news for Castleman disease.

I was even well enough to attend the 2013 American Society of Hematology meeting in New Orleans one week later. This was the same meeting where, a year earlier, we had convened the first CDCN gathering. This time we had forty-five physicians and researchers from around the world at our CDCN meeting (a new meeting attendance record), and I presented my newly proposed framework for understanding and researching iMCD. I was feeling ecstatic—not only was I healthy but I was also back to being just another researcher again. I relished the chance to be slightly boring and stand in front of a PowerPoint. No more dramatics, no more organ failure. At the end of my talk, I mentioned a “patient” with seemingly relentless iMCD who had recently improved substantially with cyclosporine and IVIg. I continued to not disclose that I was a patient myself for fear that I would be treated differently if that were known. Dr. van Rhee and those who knew I was talking about myself grinned at me from across the room.

While in New Orleans, I attended a research presentation where the final results of the international siltuximab clinical trial of seventy-nine iMCD patients were revealed. It was a huge occasion for the community—but somewhat uncertain in its implications. Dr. van Rhee was the lead investigator, and a number of other CDCN members were involved in the trial. It was the only randomized controlled trial, the gold standard test of efficacy in medicine, ever done in iMCD. This was historic. Just over a third of patients treated with siltuximab achieved a partial or complete response, compared to 0 percent on a placebo. And the drug was very well tolerated, with minimal side effects. The data were clear: Patients got better at a significantly higher rate on siltuximab than with a placebo. This trial would almost certainly lead to FDA approval of siltuximab, which would be the first ever approved treatment for iMCD in the United States and would be huge for our patient community.

But I was saddened that two-thirds of patients didn’t seem to improve measurably. I had hoped that my own disappointing response to siltuximab was idiosyncratic. Unfortunately, there were a lot of people like me. I was further surprised to learn that the levels of IL-6 rise in all patients after siltuximab is administered, whether the drug works or n

ot. That “first sign” that the drug was likely to work for me had not actually been anything at all. On the other hand, it seemed like I was on the cusp of a new breakthrough treatment, one that might just be the silver bullet for the unlucky two-thirds. It was hard not to feel like a quarterback again, responsible for the team. Answerable to the team. Now that I was feeling well enough, I was able to spend the week after the convention making final tweaks to the paper for Blood with Chris and Frits. Right after I clicked submit on the journal’s website and my focus began to recede, fatigue rushed in and another ominous thought returned: I just hope that all of our work will get out to the world to help other patients, even if I am no longer in it.

Almost exactly five months before Caitlin and I were planning to get married, the game plan completely fell apart.

Despite the new treatment and my initial improvement during this flare, it all came rushing back a few weeks later. All of it. My CRP rose above 100, and my organ function started to deteriorate once again. The fatigue was crippling. Fluid accumulated in my legs, abdomen, and lungs. I had allowed myself to think I might have beaten the beast, but I hadn’t. Once again, I went to the airport, destination Little Rock. This time, I had Caitlin by my side. Once again, my dad and sisters met me there. Once again, my blood counts plummeted. It was just like each time before. This time, however, I experienced a not-so-welcome novelty: I was failing so quickly, I fainted in the elevator at the hospital. My dad and Caitlin caught me on the way down. A fitting metaphor. On Christmas Day 2013, I approached death just as I had four times before. Nausea and vomiting overwhelmed me during brief moments of consciousness. No more time for testing new treatments. It was now really overtime five. We went back to those same damn seven chemotherapies. Deck the halls and drop the bombs.

My dad buzzed a Mohawk for me again. It didn’t give me quite the same bump in my spirits that it had the previous time or that Caitlin and my dad had hoped for. So they went to Target for a fake mini Christmas tree to see if that might lift my mood. All that was left in stock was a ragged hot pink tree. It would have to do.

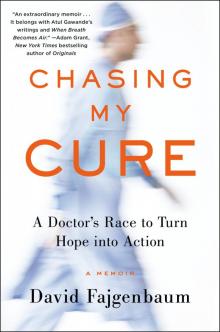

Chasing My Cure

Chasing My Cure